Asynchronous Active Learning with Perusall

After spending most of 2020 helping faculty and other instructors prepare to teach in online and hybrid contexts, I had the chance this spring to practice some adaptive teaching myself. I taught my first-year writing seminar on the history and mathematics of cryptography, a course I’ve blogged about many times in the past. Vanderbilt was largely back on campus, thanks to a rigorous COVID-19 testing regime, so my course met in person, although with masks and physical distancing and at least one student participating remotely from Arizona. This gave me the opportunity to try out some of the teaching practices and educational technologies I had been recommending to other faculty for months.

In past offerings of my cryptography course, I’ve had students read articles and listen to podcasts, usually about the privacy and surveillance topics in the course, as preparation for class. For years, I would have students blog about these media before class, and I would use the students’ blog posts to shape and inform class discussions. This spring, I had decided not to use my long-running course blog so I could experiment with Microsoft Teams as a class communication platform, to see if it would help create more social presence than the course blog. I had also decided that most of the Wednesday class sessions in this MWF course would be asynchronous, primarily for childcare reasons but also to try my hand at asynchronous instruction.

All this meant I was looking for ways to engage my students in active learning, online and asynchronously, without using my course blog. Teams gave me some options for this, and I’ll write about that at a future date. Today, however, I want to share how I used the social annotation platform Perusall to engage my students. Perusall allowed me to share a variety of “texts” with students, including news articles, podcast episodes, and YouTube videos, and to invite students to annotate those texts collaboratively. Students could highlight a passage in an article or point to a spot in a video and leave a comment for others in the course to read. Students could respond to other students’ comments, tag other students or me in their posts, flag a comment for me as a question to respond to, and more.

I had known about Perusall and the other leading social annotation tool, Hypothesis for several years and I had even written about social annotation in my 2019 book. I hadn’t actually used social annotation with learners until the 2020 Online Course Design Institute that my teaching center hosted. We used Perusall for a couple of asynchronous online activities in that institute, and faculty reaction to the tool was very positive. In fact, there were dozens of faculty on my campus who started using Perusall last fall because of their exposure to it in the OCDI last summer. I decided I should join that group this spring and see how I could use the tool with student learners.

The first asynchronous day of the course, Wednesday, February 3rd, served as the students’ introduction to Perusall. I asked students to read and annotate three recent news articles about surveillance and privacy. To add a news article to Perusall, you have a couple of options. You can give Perusall the link and ask it to create a copy of the article, or you can save the article yourself as a PDF and then upload that PDF to Perusall. I found the latter option was a little more reliable, since paywalls sometimes interfered with the former option.

Since this was the students’ first time using Perusall (at least in my course), I suggested a few different annotation “moves” they could make as they read the articles:

- What is unclear or confusing about the article? You’re welcome to highlight a sentence or phrase and ask questions about it.

- What do you find surprising within the article? You might highlight a passage and comment on why it surprised you.

- What arguments presented in the article do you find compelling… or problematic? You might highlight a quote and comment on why you agree or disagree with it.

- What connections can you draw between the article and other things we have read or discussed in this course? You can highlight something in the article and comment on the connection you see.

Students responded well to the activity and to these suggestions, contributing dozens of annotations to the articles and even occasionally responding to each other’s comments. It was the second week of classes, so they were probably eager to make a good impression and not yet too tired, which likely helped. But I was pleased with their engagement, both on Perusall and on Teams, where I asked them to respond to a couple of summary prompts about the articles. Since this activity was meant to take the place of a face-to-face class, I responded directly to student comments on Perusall and Teams, instead of debriefing with the class on Friday. I did, however, wait until Thursday to weigh in, so that students would have more time to process the articles independently.

For the next week’s asynchronous day, Wednesday, February 10th, I provided students with different media to annotate in Perusall: a student-produced episode of the course podcast about the Zodiac serial killer and a YouTube video explaining how one of the Zodiac’s encrypted messages was recently deciphered. I couldn’t believe my luck finding this video; not only had a long unsolved mystery in cryptography been solved just week before my course started, but one of the solvers made a very clear explanatory video about the solution!

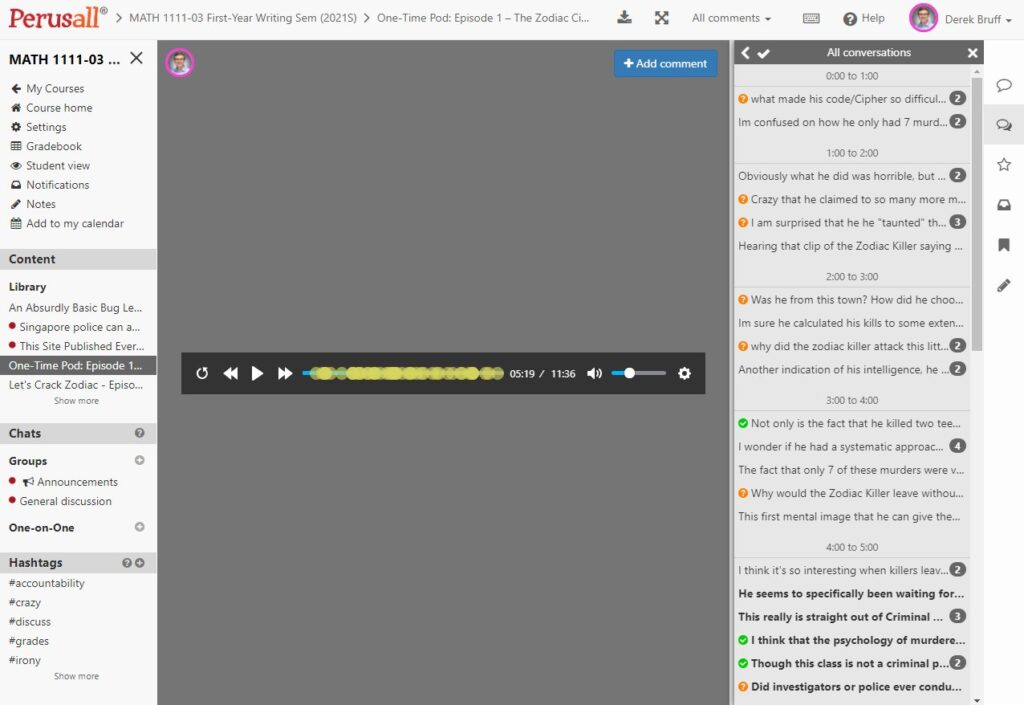

Adding a YouTube video to Perusall is dead simple–you just give it the URL and Perusall does the rest. For podcasts, you have three options: search for a podcast (using, I think, the Apple podcast library), submit the RSS feed for a podcast, or enter a direct URL to an MP3 file. Since I’m on #TeamRSS4ever, I added the RSS feed for the course podcast and quickly selected the episode I wanted imported to Perusall.

The annotation interface for both podcasts and videos is similar. Anytime while listening or watching the media, you can pause and add a comment, which is then attached to a timeline. You can see little dots on the timeline representing comments and use them to navigate to that point in the media. The only problem I found was that you can’t watch a video or listen to a podcast while also reading annotations. That is, once you bring up an annotation, the media pauses. This made reviewing students annotations a little cumbersome, but I could alternate between the media and the annotations well enough.

For the following asynchronous day, Wednesday, February 17th, I went in yet another direction with Perusall. Since the novel my students were reading, Little Brother by Cory Doctorow, was available as a PDF under a Creative Commons license, I loaded the entire novel to Perusall for the students to annotate as they read. To help students make interesting annotations and to give students a reason to read each other’s annotations, I gave each small group in the course a different annotation move to make. Note that the student groups in this course were persistent and called “cipher bureaus” after a 20th century term for codebreaking teams.

- Cipher Bureau 1 (Pretty Bad Privacy) – I want you to focus on key quotations from the book. What are the quotes (from Marcus or other characters) that make important arguments or sum up a character or just caught your attention? In your annotations, explain why the quote you highlighted seems important.

- Cipher Bureau 2 (Puzzle Pals) – You are the creative connectors. I want you to highlight passages that you can connect to other topics we’ve discussed in the course, or to topics in the wider world of cryptography. In your annotations, explain the connections you see.

- Cipher Bureau 3 (Cipher Squad) – You get to be devil’s advocates. Your job is to argue with statements made by characters, including Marcus, in the book. Highlight statements and then in your annotations explain why someone might disagree with those statements.

- Cipher Bureau 4 (The Zodiacs) – You are the creative questioners. I want you to pose questions in your annotations inspired by the passages you highlight, particularly questions that connect to the book but also go beyond the book.

These different roles–passage master, creative connector, devil’s advocate, and questioner–were based on roles described in “Using Structured Reading Groups to Facilitate Deep Learning,” a 2011 Teaching Sociology article by Heather Parrott and Elizabeth Cherry. I really like their approach to small group discussions of readings, where each student has a different and useful role to play. These roles guide their reading and class preparation and help ensure every student can contribute to group discussions of the readings. I’ve recommended these roles time and again in faculty workshops, and I was excited to see how well they worked in this annotation activity.

Other asynchronous days during the semester repeated some of the above approaches, with students annotating texts, podcast episodes, and videos and often responding to summary discussion prompts over in Teams. The Perusall activity for Wednesday, March 31st, was a little different. Students were starting to work on their episodes for the course podcast, and I wanted them to listen to some sample audio pieces that would help them prepare for their own production work. In one activity, I shared episode 8 (“Crossfire”) of the Whirlwind podcast on Perusall and asked students to annotate it. This time, I provided somewhat different prompts for their annotations, ones that pointed to elements of the grading rubric I would be using for their own podcast episodes.

- Hard Questions – What hard questions does the podcast episode raise about the role of cyberwarfare in the 21st century? (A hard question is one that doesn’t have an easy answer, that permits lots of different competing perspectives, and that takes some research to figure out.)

- Interestingness – What moves do the podcast producers make to interest listeners? Consider not only the creative use of audio, but also the ways the content is explained or structured.

- Accessibility – How do the podcast producers make the more technical matters of the podcast content clear and understandable to listeners?

This was one of several “scaffolding” activities that were part of the podcast assignment, and it worked well to help students think about moves they might make as podcast producers.

Then on Wednesday, April 21st, to help students get ready for their final paper assignment, I shared with them a de-identified draft paper a student had submitted back in 2019 for the same assignment. I asked students to annotate the draft paper–letting them know that this wasn’t the student’s final version–focusing on elements that worked and suggestions for improvement, in both content and clarity. As with the podcast assignment, I wanted students to experience samples of the kind of product they were creating for their final paper, a traditional research-based argumentative essay. I’ve seen hundreds of such essays, but I know my students have seen very few, and I think it was helpful to have them annotate and critique a sample student paper that was known to need improvements.

I should mention my approach to assessment of student work on Perusall. The platform has a fairly sophisticated auto-grading tool that can be set up to look at things like the number of annotations a student makes, how well those annotations are distributed throughout a text, how often a student’s annotations are upvoted by other students, and even the quality of a student’s annotations using some kind of black-box text analysis algorithm. That’s all very clever, but I didn’t really want my students worrying about earning points on their annotations in such a granular way.

Instead, I had students self-assess their contributions, as I’ve done in previous offerings of the course. Students rated themselves from 0 to 10 holistically on their contributions to the course learning community through Perusall, Teams, and any other online tools we used, providing me with their rating and a paragraph or two of justification. For a small class like this, where students are generally motivated to participate, this self-assessment has been sufficient to motivate the kind of online participation I like to see from students, and it worked again this semester.

Looking back, I’m very happy with how Perusall supported online and asynchronous active learning for my students this spring. I hope it’s clear from the activity descriptions above that the platform can flexibly support a variety of content and activities. Set-up was a breeze thanks to Perusall’s integration with Brightspace, our course management system, although I heard that faculty who wanted student grades to flow back into Brightspace had to very careful how they set things up. Since I wasn’t worried about that, my Perusall experience was problem-free.

Next time, I’ll try using Perusall’s assignment tool–not for the auto-grading, but for the analytics Perusall provides on student contributions. I think that would be particularly useful in larger classes, even without the auto-grading. I’m also hoping to experiment more with using Perusall during synchronous class sessions. I tried that once this spring, having students highlight and tag passages in a reading that they wanted to include in the class discussion, and it worked fairly well. I’d like to see what else I can do with synchronous use of Perusall.

I hope this post has provided some ideas for how you might use Perusal and similar tools in your teaching! Feel free to share more ideas in the comments or over on Twitter, where I’m @derekbruff.