Summer Reading: The Sketchnote Handbook by Mike Rohde

If you follow my blog or Twitter account, you probably know that I’m a fan of sketchnotes. Sketchnotes are notes taken during presentations or panels that combine doodles and diagrams and text and typography to capture ideas visually. I learned about sketchnotes a few years ago when I started reading more about visual thinking, and I first tried my hand at sketchnoting back in 2011. I’ve found the practice incredibly useful, both for focusing my attention during talks and for capturing ideas from talks for later reference and use. You can see some of my conference sketchnotes over on Flickr, and you can find my sermon sketchnotes (yes, I sketchnote at church!) on my “Doodling in Church” blog.

Last December, I picked up Mike Rohde’s new book, The Sketchnote Handbook. I’ve learned a lot about sketchnoting from looking at the notes shared on Sketchnote Army, a blog created by Rohde, and I wanted to see if I could improve my craft by reading Rohde’s “illustrated guide to visual note taking.” Rohde’s book is an excellent introduction to sketchnoting, and I believe it’s helped me create more visually interesting notes that do a better job of capturing key ideas from the talks I attend. If you’re interested in getting into sketchnotes yourself, I highly recommend it.

Last December, I picked up Mike Rohde’s new book, The Sketchnote Handbook. I’ve learned a lot about sketchnoting from looking at the notes shared on Sketchnote Army, a blog created by Rohde, and I wanted to see if I could improve my craft by reading Rohde’s “illustrated guide to visual note taking.” Rohde’s book is an excellent introduction to sketchnoting, and I believe it’s helped me create more visually interesting notes that do a better job of capturing key ideas from the talks I attend. If you’re interested in getting into sketchnotes yourself, I highly recommend it.

Rohde begins by making a persuasive argument for the value of sketchnoting. Like Rohde, I used to take copious amounts of text notes on talks and presentations, filling up pages and pages in legal pads. And like Rodhe, I almost never looked at these notes after the talks were over. These days, I use sketchnotes to distill the main ideas of a talk into one or two pages of visual notes that I actually remember and reference. Rohde points out that the practice of sketchnoting is supported by cognitive science, particularly dual coding theory. Our brains process verbal and visual information using separate “channels.” Taking text notes is a bit like using half your brain power. Capturing ideas in both words and pictures uses more of your brain, helping you better understand and remember those ideas. Sketchnoting isn’t the only way to listen actively during a talk (I find that live-tweeting helps me do that, too), but it’s a useful method, and one that produces a product worth sharing and using down the road.

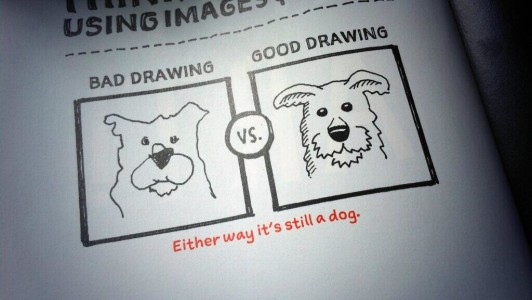

Some people are hesitant to try their hand at sketchnoting because they feel they “can’t draw.” Rodhe points out, as others have, that we all drew as kids and that the quality of drawings we produced as kids are completely sufficient for sketchnotes. “Kids draw to express ideas,” writes Rohde. “They don’t worry about how perfect their drawings are, as long as their ideas are conveyed” (p. 15). Later in the book, he distinguishes between structure and art. Sketchnotes can feature simple artwork or fancy artwork, but it’s the structure of the notes that matters most. That’s why simple lines, circles, arrows, and stick figures can be just as useful as more highly rendered elements of sketchnotes.

I should point out here that The Sketchnote Handbook is one giant sketchnote. Rohde combines words and pictures throughout the book very effectively to communicate his ideas and techniques. The book is full of practical advice for the novice sketchnoter. Here are a few takeaways that I’ve already found valuable:

- Live sketchnoting requires you to “cache” idea. Sometimes you have to listen for several minutes, processing what the speaker is saying, before you’re ready to put pen to paper. Holding a few ideas in your head while you make sense of them and see where the speaker is going is a key skill.

- Sit strategically. Look for a seat near the middle of a row, so you’re not disturbed by latecomers, and try to sit under a light source so you can see your notebook clearly. I follow this latter advice all the time at my church, which likes to keep the room lights low during the sermons.

- As the talk begins, consider what kind of pattern your notes will take as they fill up the page. Rohde identifies seven common sketchnote patterns: linear, radial, vertical, path, modular, skyscraper, and popcorn. Some talks lend themselves to some patterns more than others, and you can often predict this based on what you know about the format, speaker, and description.

- Develop your visual library, the doodles, font styles, and icons you use regularly in your sketchnotes. Rohde’s book is full of inspiration for doing so. I’ve already added a couple of extra type faces and arrow styles to my sketchnotes thanks to what I’ve seen in The Sketchnote Handbook. The book includes examples from Rohde’s sketchnotes, as well as sketchnotes from at least a dozen other practitioners throughout the book. He also includes a set of visual exercises in his last chapter for practice.

If there’s a fault in The Sketchnote Handbook, it’s the lack of attention to the selection of visual metaphors and the use of schematic diagrams to represent relationships. Rohde spends a page on metaphors, but his examples don’t shed much light on how one would go about identifying a useful visual metaphor. I’ve found Garr Reynolds’ Presentation Zen useful for selecting photos that represent ideas metaphorically, and much of that practice translates to sketchnotes. And while Rohde offers great advice on structuring a page of sketchnotes using his seven patterns, he doesn’t go into how schematic diagrams using circles, boxes, and lines can effectively convey complex relationships to the extent that Dan Roam does in The Back of the Napkin.

Even so, I would recommend Mike Rohde’s handbook to anyone interested in getting started with sketchnotes. You can find out more about the book on his homepage, and you can view a sample chapter online. Rohde has set up a Flickr group for readers of his book to share their sketchnotes, too, which has served as a nice way to develop a community around the book and the practice.